Why the UK must end climate catastrophism

The climate catastrophe movement’s models and data show that predictions of an alarming temperature rise in the Earth’s climate are wrong. This error is destroying our ability to reform our country.

THE CLIMATE CATASTROPHE MOVEMENT’s hypothesis is this: carbon dioxide causes the Earth’s temperature to rise; the amount of carbon dioxide we produce is having a significant warming effect on the Earth; to prevent a large number of very unpleasant things from happening, we must significantly reduce our carbon dioxide production.

This hypothesis is unproven. The conclusion that it draws—that we must accelerate the contraction of energy that is already underway—is reckless. Yet this conclusion now informs the official energy policy of the United Kingdom.

In this essay, we’ll examine why it is wrong, and why its policy recommendations must immediately be overturned.

But first, let’s recall a few basics that are often overlooked by climate catastrophists.

The climate catastrophe hypothesis is rooted in science, not religion. In science, all knowledge is provisional. Because all knowledge is provisional, we must be skeptical of every hypothesis that claims to be true. Every hypothesis—even gravity—must survive continuous attempts to falsify it. We aren’t ashamed of being sceptical. In science, the most sceptical party—the party that leads the effort to falsify a hypothesis—is the party that is advancing it. Why? Because surviving continuous falsification attempts is the only way that we can have confidence in scientific theories, or in discovering their defects. “Settled” science is an oxymoron, like “social distancing”. “Denial” is an accusation made by priests. Not by scientists.

Climate catastrophism requests immunity from the scientific method. In this essay, we deny the request.

Climate science is complex. But we don’t need to be experts to be able to interrogate its claims. We don’t need to be able to ride a motorbike to know it won’t go anywhere with a flat tyre—we just need to have ridden a bicycle. With a little study, we can understand well enough the physics, the chemistry, the earth science, the statistical methods, and the computer modeling techniques that climate catastrophism derives its hypotheses from. We’re as well placed as anyone else to look at their evidence, to evaluate their arguments, to ask questions, to make our own conclusions. And to spot a naked Emperor.

This isn’t conceited: extraordinary claims—such as the one that we should immiserate ourselves and our children on the basis of guesses about the distant future temperature of the planet derived from representationally incomplete models of the Earth’s poorly understood climate—demand extraordinary evidence. Whatever evidence they have, it should be extraordinary.

It’s not.

Climate catastrophism falls at the first hurdle: rising carbon dioxide does not produce rising temperature. Specifically, there is no observable relationship (what statisticians call a “correlation”) between the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the temperature of the atmosphere. We know this from ice cores, which allow both atmospheric temperature and carbon dioxide concentration over the last 425 million years to be estimated.1 In that time, there has been every combination of high and low temperature and carbon dioxide, and several occasions when rising carbon dioxide has accompanied falling temperature.

It is true that carbon dioxide affects temperature. But then, it’s also true that a cucumber sandwich affects my weight. Just not very much. That shouldn’t surprise us: carbon dioxide makes up about 0.04% of the atmosphere, and we increase the total annual natural emission of it by only 4%.

There are very many other processes that affect the earth’s temperature, including water evaporation, cloud formation, ocean currents, meridional transport, sunspot activity, and the gravitational effect of the movement of the planets around the sun. Carbon dioxide, and our contribution to it, isn’t a terribly powerful one, relative to others. Have you tried walking the wrong way up an escalator? That’s like carbon dioxide fighting against these oppositional processes. Sometimes it’s with them. Sometimes against. But it’s why there’s no correlation.

Then there is the problem of trying to quantify the effect of our carbon dioxide emissions relative to the 96% of it that is natural. The climate record shows that Earth’s temperature changes naturally over a large range. We’d like to find out how much—if any—of the current change is caused by us. We can’t measure it. So we have to try some other way.

Normally, we’d find out by making a model of the physics, and calculating it directly. That’s how we build highly accurate oil reservoir models, for example.

Climate scientists can’t do that. To make a model, you need to know three things:

(a) all of the things that drive the property you’d like to predict

(b) the physics of all of those things and

(c) how to represent all of that physics in a computer.

I listed some things that drive climate. There are many others. We just don’t know what they are. And if you don’t know what’s causing something, you can’t predict what the state of that something will be in the future.

Many of the things that we know drive the climate, we can’t model. For example, we know that water vapour and cloud formation is a much stronger force than carbon dioxide in affecting heating. But we don’t understand the microphysics of cloud formation—we can’t predict when and where clouds form.

And the whole climate system is an example of what in maths is called a “non-linear” system—one in which small changes in the input create large and unpredictable changes in the output. This is sometimes called “the butterfly effect”—inside the model, a butterfly flaps its wings in Tokyo and a thunderstorm breaks out in Edinburgh. We’ve no way of representing non-linear systems in computers. It’s why you don’t get an accurate local weather forecast more than a couple of weeks out. It doesn’t magically become easier when you’re trying to forecast global climate in 100 years time .

So, since they can’t identify all of the things that drive the climate, and they don’t know the physics of many of the things they can identify, and they can’t represent the result in a computer, here’s what they do instead.

You can get almost anything to correlate with anything else. You just need a few knobs to adjust. Fun things to practice on when I was going through modelling school were womens’ skirt length vs. the stock price, and cheese sales vs. Nicholas Cage movie ratings. Climate modellers assume (wrongly, remember) that carbon dioxide and temperature are strongly related. They replace all of the climate physics that they don’t know with a black box with a few knobs on it. Then they tweak the carbon dioxide/temperature knob—what they call “climate sensitivity”—until “things line up”. Whatever the setting that the climate sensitivity knob is at when things line up, is the number they guess is the climate sensitivity. But it’s just a random number.

It’s easy to show that the estimate for climate sensitivity produced by models that wrongly assume that carbon dioxide and temperature are strongly related is a random number.

When you’ve built a model for which you have historical data—say, surface temperatures since 1850—you can initialise it to some time in the past and see if it predicts that historical data. We call it “backcasting”—forecasting the past. If your model can’t predict today from yesterday, it certainly can’t predict tomorrow from today.

The predictions of catastrophe are made by a large number of official models. These are called “Global Circulation Models”, and the climate scientists regularly compare them in an international project called “the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project”. They’ve just published their 6th set of models.

We can divide these official models into three groups: the ones that predict “disaster”; the ones that predict “general unpleasantness”; and the ones you’d want to take a second look at, just to make sure.

When you initialise them all to the climate in 1980, set them running, and see what they say about 2023, the “disasaster” and “general unpleasantness” models produce comedy Hollywood disaster movie temperatures.2 We can throw those away. There will be no catastrophe, or even general unpleasantness.

You could stop reading now. But it gets even more interesting.

Next, we can take a second look at the least alarming ones. In the backcast, what we are testing is how well the models fit a record of surface temperatures. It turns out, when you plot that data as a spatial plot of how temperature has changed, you get a beautiful map of all the big cities, airports, industrial centres, and oil and gas regions where you’ve been flaring gas for decades. The temperature in the dataset has risen. It is warming. It’s just not the climate that’s warming.

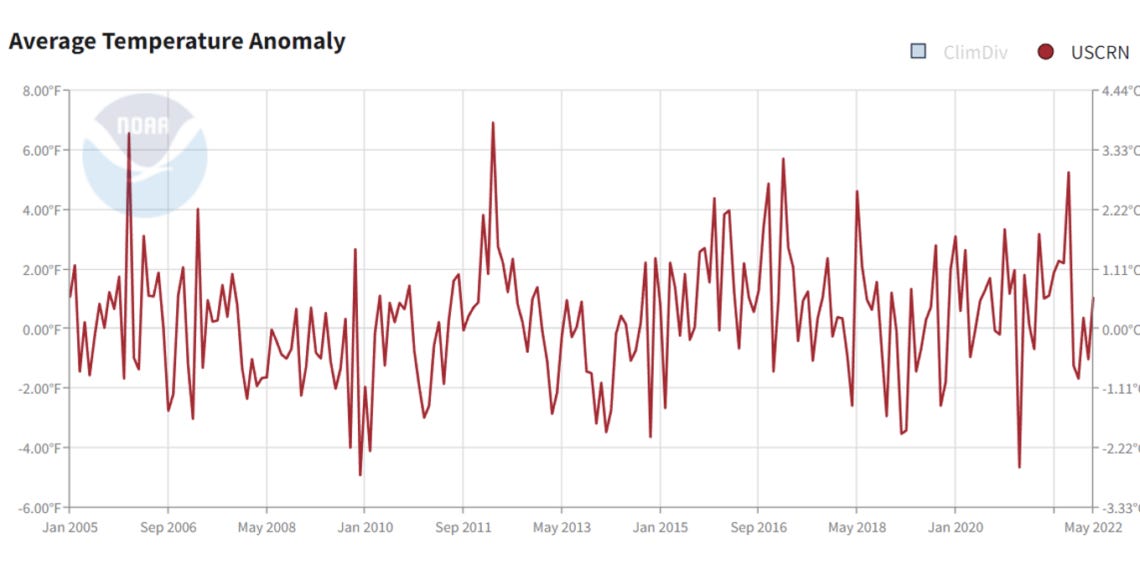

As it turns out, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) publishes a checklist of criteria that surface temperature stations must meet to ensure that they aren’t contaminated by heat biases caused by proximity to runways, large heat generating machinery, and buildings. And it further turns out that 96% of monitoring stations in the USA fail to meet the criteria.3 And it further, further turns out that NOAA maintains a temperature data subset based on the 4% that do—the "U.S. Climate Reference Network".4 And it further, further, further turns out that the temperature rise in that dataset is about the rate it’s been rising for centuries as we recover from the recent Ice Age.

And, not surprisingly, when we backcast the models against that dataset, the only ones that match are the ones that assume negligible rate of human warming.

The earth is warming. But our carbon dioxide is not having a significant warming effect on the Earth. We do not have to reduce our carbon dioxide production to try to control it.

This is an incredibly important conclusion.

We don’t reject the climate catastrophe hypothesis because we don’t want a better world, for ourselves, and for our children. All of us hope for that. And many of us who do reject the climate catastrophe hypothesis share with its believers the recognition that increasing energy and resource scarcity presents a very serious threat to that hope, and that we need a new living arrangement.

The question is: how? And the problem is that, to avoid death on an epic scale from cold, malnutrition, disease, and poverty, whatever this new arrangement is will still require an equally epic amount of energy to keep seven billion humans alive. We'll need even more than we're currently using while we build out whatever this new arrangement is. Every energy transition in human history has.

The bulk of that energy is currently provided by oil and gas. The thermodynamically absurd project — "renewable energy" — that strains to replace it with weather dependent, low gradient sources, spawned by the climate catastrophe hypothesis’ claim that we must “reduce our emissions”, is exactly—exactly—the wrong thing to do.

By allocating our precious stocks of remaining high quality energy to building short lived energy scavenging devices, we are accelerating the pace of energy contraction, and robbing viable projects of the energy they need to implement them.

And by extending our production of imaginary money to fund the pointless reduction of an atmospheric trace gas, we are hastening the collapse of our financial system.

To stand any chance of making an orderly retreat to a society built around high grade alternatives to hydrocarbon, we need — immediately — to abandon this reckless “Net Zero” energy policy. Our future, and the future of our children, depends on it.

See, for example, Davis, W. ‘The Relationship between Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Concentration and Global Temperature for the Last 425 Million Years’. Climate 5, no. 4 (29 September 2017): 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli5040076.

Scafetta, Nicola. ‘CMIP6 GCM Ensemble Members versus Global Surface Temperatures’. Climate Dynamics, 18 September 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-022-06493-w.

Watts, Anthony. ‘Corrupted Climate Stations’. The Heartland Institute, 27 July 2022. https://heartland.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/2022_Surface_Station_Report.pdf.

A first class essay - short, very informative, punchy and to the point.

Well presented facts and drawn along with interest to the conclusion. Learned that we can't predict cloud formation....(unless made by chemtrails.... long thin 'clouds' that spread to form grey canopies), and, about 'Global Circulation Models'. The reductionism to Co2 by particular individuals and groups across Continents, is one giant bluff to mankind and one giant step back to a Darker Age.