The physics of Net Zero

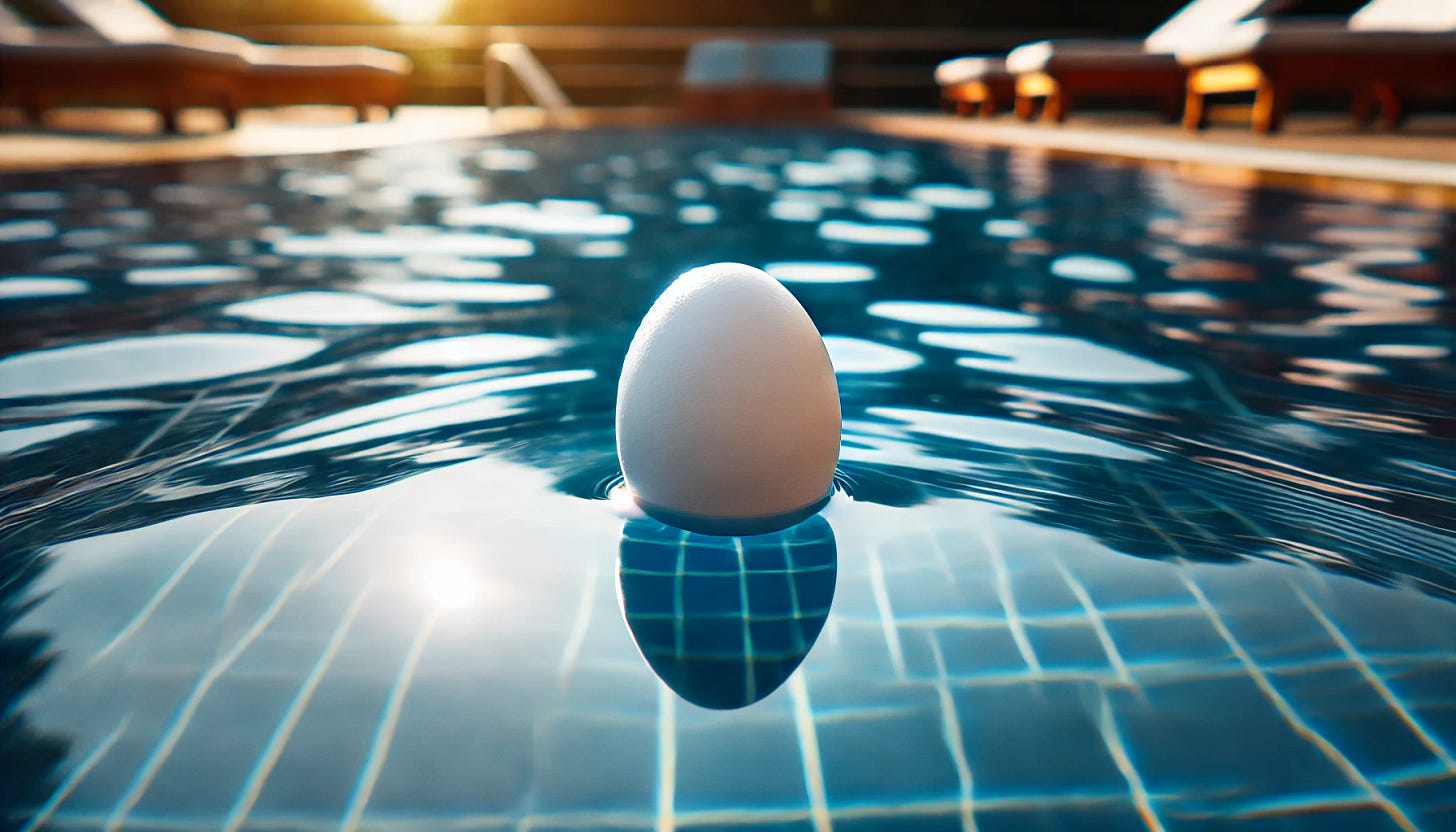

You can't boil an egg in a swimming pool. Or run Britain on breezes.

“[Clean tech is] a perfect example of a 10x exponential process which will wipe fossil fuels off the market in about a decade” — Tony Seba. Stanford Economist, 2017

“Ye cannae change the laws of physics, Captain!” — Montgomery Scott. Chief Engineer, USS Enterprise

Physics, not imagination, or determination, limits what an energy transition can achieve. In this week’s essay, we look at energy’s most important physical property — gradient — to understand why running Britain on “renewable energy” is physically impossible.

THE BELIEF THAT we can power an advanced industrial economy on occasional sunbeams and summer breezes is central to Britain’s “Net Zero” energy policy. This fundamental misconception originates in the confusion in the minds of physically illiterate economists who, observing computer and information technology disruptions in Silicon Valley, fantasise about similar disruptions in the energy sector.

In the abstract world of information, bits and bytes don’t have mass, inertia, or friction. They aren’t limited by gravity, or by thermodynamics. Efficiency can increase exponentially, endlessly driving down size and cost.

The world of wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries, on the other hand, is limited by physics. Those limits are hard, and they are non-negotiable. Of these, the most fundamental limit is energy gradient. It is wind and solar’s very low energy gradient that creates an inherent and insurmountable barrier preventing the replacement of hydrocarbon and nuclear with them.

TO RUN AN advanced industrial economy like Britain’s, we need a vast amount of energy. Enthusiasts of “renewable energy” point out, correctly, that there is a vast amount of energy in wind and sunshine. “It’s a no brainer”, as the consultant would say.

But while energy quantity is necessary, it’s not sufficient.

There’s much less energy in an egg pan of boiling water than there is in a swimming pool.1 After four minutes in the egg pan, useful chemical and physical reactions have taken place. Proteins have denatured and coagulated, unfolding, reforming, and aggregating into new structures. Sugars and proteins have reacted, forming new flavour compounds. Sulphur and hydrogen have combined to create a smell. And the egg’s internal pressure has increased, cracking the shell. Much work has been done.

After a whole day in a swimming pool, we’ll still have a cold, raw egg.

Clearly, something else is going on.

To do work — to carry out operations that have physical value in our economy — we also need an energy gradient. An energy gradient is a change in energy from one place to another. It might be the difference in gravitational energy between the top of a hill and the bottom. Or in chemical energy between a battery and a toy. Or in thermal energy between hot water and an egg.

It is the energy gradient — the difference in energy between two places — that causes work to be done. A skier rushes to the bottom of the mountain. A toy monkey bangs its drum. The chemical and physical structure of an egg changes.

How do we make an energy gradient? By creating a difference in energy density. Energy density is the amount of energy stored per unit of “stuff”. While there is much more energy in our swimming pool than in our egg pan, that energy is spread out through 2,500 cubic meters of water. The energy in our egg pan, although less, is spread through only 200 cubic centimetres. The egg doesn’t “see” the energy at the other end of the pool. It “sees” the energy gradient at its shell. And changes.

Energy density is a property of an energy source, and is what limits the usefulness of that energy source.

Britain’s energy system comprises a large number of energy sources. Each source creates an energy gradient between itself and the things we want to do work in — our factories, our fields, our homes, our hospitals. The total gradient in our energy system is the combination (but not the sum — more in a moment) of the gradients of all of the sources in our system.

These different sources — nuclear, coal, oil, gas, wind, solar — each have very different energy densities.

So if energy density limits the usefulness of each as an energy source, what factors limit their energy density?

THREE FACTORS CREATE differences in density between these generators.

The first density factor is the primary source of the energy. Nuclear and fossil energy has very high energy density. That’s because breaking atoms (in nuclear fuel) and chemical bonds (in fossil fuel) releases a huge amount of previously stored energy. Solar and wind energy has very low energy density. That’s because it’s the radiant energy2 that has been weakened by spreading out as it travels the vast distance from the sun. It’s so weak, in fact, that at the height of summer here in Britain, you can run around all day with your shirt off and still be pale blue at supper time.3

The second density factor is time and space compression. Radiant energy in our environment is diffuse, like the thermal energy in our pool, and is only available to us “in real time”. In the fossil energy in our petrol tank, we’re benefitting from millions of years of sunlight that has been captured over millions of square miles of forest and ocean, and processed, concentrated, and stored for us for free by quintillions of Joules of geological energy. This free compression of time and space vastly increases fossil fuel’s energy density.

The third density factor is net energy. It takes energy to get energy. Gas wells have to be drilled. Solar panels have to be made. The effective density of an energy source is reduced by the quantity of energy required to obtain it. Low density “renewable energy” devices are the high-technology products of the vast, high density hydrocarbon and nuclear powered machine called “the global industrial manufacturing system”. Deducting the manufacturing energy cost from a nuclear or fossil fuel source doesn’t change its net output much. Deducting it from a wind or solar source wipes it out. Where fossil and nuclear sources provide 30 units of energy for every unit of energy we invest obtaining them, wind and solar provide (at best — again, more below) single digits. The result is a much lower density source.

In summary. Fossil and nuclear fuels release energy by breaking atoms and chemical bonds; they “compress time and space”; and obtaining them takes relatively little energy. They are high density, producing high energy gradients.

Solar and (ultimately) wind energy is obtained from radiation; it’s scavenged in real time; and obtaining it requires a huge amount of energy. They are are low density, producing low energy gradients.

So why can’t we just string low density sources together to make high density sources?

THE LARGER THE energy gradient between two places, the more work gets done. The lower the gradient between two places, the less work gets done. Adding lots of low gradient energy sources increases the quantity of energy available to us. It doesn’t increase the gradient of that energy. Our egg didn’t boil in an olympic sized swimming pool. Two olympic sized swimming pools have twice the amount of energy. It won’t boil in them, either.

Both the ski run, and the queue to the ski lift, have an energy gradient. The gradient of the ski run is so large that we try to avoid getting killed falling down it. The gradient of the ski lift queue is so low that we try to avoid falling over while we shuffle along it. The queue has a height difference. If we placed 1,000 of them end to end, we might create the height difference of Mont Blanc. But it’s still a long walk. We can’t ski on a ski lift queue. We can’t ski on 1,000 ski lift queues, either.

A “renewable energy” consultant might say: “But look at all the energy in my swimming pool. I can concentrate it at one end, and boil my egg!”. To which we might say: “Concentrate it with what?”. To which she might say: “With a device that works like the opposite of a fridge”.4 To which we might say: “A device made with, and powered by, energy obtained from where?” To which she’ll say: “...”

And this is where it gets interesting.

We make low gradient energy solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries with high gradient energy from hydrocarbon and nuclear fuels. There’s no other way. The delivery of a low gradient energy wind turbine made using high gradient energy is very much like the delivery of a baby by a stork: a lot of uncomfortable details have been omitted, and it’s all a bit implausible.

If we draw a boundary around two wind turbines that have been delivered by a stork and strung together, an apparently miraculous thing happens: inside the boundary, their combined energy gradient increases. It’s as though we’ve added two ski lift queues together and, instead of getting longer, the queue got steeper! How can this possibly be?

Well, we’ve enough knowledge of the physics of energy gradient and density now to work it out. In building their wind turbine from high gradient nuclear and hydrocarbon energy instead of from low gradient solar panels and wind turbine energy, they’ve in effect used a second, hot (and hidden)5 swimming pool. They’ve boiled an egg. But the energy to boil the egg didn’t come from the weak, diffuse energy in the first swimming pool. It came from split atoms and million year old sunlight in a second one.

But if “Net Zero” was implemented, the energy to build the solar panel and wind turbine would have to come from the solar panels and wind turbines themselves. It would have to come from the only swimming pool we’d have. And then adding windmills together wouldn’t increase their gradient. The ski lift queue would just get longer.6

Net energy. Low gradient. Sadly, with ultra diffuse sources, as with friction in the charlatan’s perpetual motion machine, there’s no avoiding it. A gas fired power station is like the egg pan and ski black run in our thought experiments. A wind turbine built with energy from wind turbines is like the swimming pool and the ski lift queue. String as many windmills as you like together, and you’ll never get the energy gradient of a gas fired power station. Even when the wind is blowing.

WE’VE ARRIVED. WE’RE able now to understand the simple physics of why Britain can’t just string lots of wind turbines and assorted other low energy density gadgets together and hope to power our economy. Which is to say — survive.

The economic processes that our lives literally depend on — mining, refining, heat forming, chemical processing, steel production, cement production, semiconductor manufacture, crop fertilisation, transportation, refrigeration, assembly, operations, maintenance, repair, replacement — all require high energy gradients to create the necessary physical transformations.7 The global industrial manufacturing system — that creates wind turbines and solar panels — requires an extremely high energy gradient.

If we ever foolishly tried to run our country on low density energy sources like sunbeams and summer breezes, then we’d be left looking at the industrial equivalent of a cold, raw egg. I described where that path takes us — specifically, our financial system and pension — in my last essay.8

Note that this has nothing to do with the fact that the wind regularly doesn’t blow, and the sun regularly doesn’t shine.9 Those problems, while astronomically expensive to address are, theoretically, at least, addressable.10 No — this is a problem in the fundamental physics of energy production itself. And, as Scottie wisely said: “Ye cannae change the laws of physics, Captain”.

In Britain, the insane energy policy equivalent of trying to boil an egg in a swimming pool has a name. It’s called “Net Zero”.

We must Say No to Net Zero. But time’s running out. If you agree, please share this email with your friends.

If this isn’t obvious, then imagine throwing two egg pans of boiling water into the pool. Now there’s at least twice as much.

Wind is not radiant energy, but rather mechanical (kinetic) energy that arises from the interaction between radiant solar energy and the atmosphere. I’m simplifying a little here for brevity using the conservation of energy principle, and the assumption that wind energy can’t exceed solar energy over a sufficiently large area and time period.

A major source of confusion in narratives about renewable energy is that the energy from the sun, being highly ordered and coherent, is an extremely efficient energy source (in the language of physics, it has very low entropy). The problem is that, to be useful, this energy has to be harvested and rendered compatible with the economy’s stringent input requirements—collected, converted, regulated, stored, and transmitted. The average continuous power output of a square meter of land in the UK, taking into account diurnal variation, cloud cover, and conversion factors, is about 17W. The colossal energy cost of the harvesting process demolishes that output, destroying its gradient.

A fridge is just a heat pump. Run it one way, and you move heat out of a box. Run it the other, and you move heat into it.

The “renewable energy” industry uses this trick to manipulate energy calculations to make it appear as though low gradient “renewable energy” devices return energy. It works like this: when the high gradient energy required in the manufacture, operation, maintenance, and endless replacement of their devices and the devices comprising their manufacturing system and the devices that make the devices comprising their manufacturing system and the devices that manufacture those devices is excluded, the energy return ratio of their devices goes up. When it is included, the return ratio goes negative i.e. their devices return less than was used to create them. In every study you will see, they exlude most of the energy not employed directly in the manufacture of the device.

The “renewable energy” consultant will then claim that, as long as low gradient devices return more energy than is required to obtain it, we can simply scale them up and concentrate the difference. But, when this physics-free notion collides with exponential maths, we run quickly out of Britains to mount the devices, and Congo child slave labour to mine the lithium and cobalt. See my essay “On the edge of a cliff" (29 June 2024)

They also require a vast array of materials, such as the advanced composite carbon fibres that made windmill blades possible, that are made from hydrocarbon and, as far as we can tell, can only be.

See my essay “Net Zero and the end of our pensions” (27 July 2024)

Our “renewable energy” consultant might say: “I shall collect all the energy from my wind turbine when I’m not using its energy in a battery, and use it later”. Then she’ll plug her battery factory into her battery, and wonder why there’s nothing left to run her heating system with that evening.

The UK’s prestigious Royal Society tried recently to estimate the cost of long term storage that would be required to prevent blackouts in an electrified UK economy. After correcting for the error in their cost model, it’s around £1 trillion. See: Llewellyn Smith, C. (2023) Large-scale electricity storage. The Royal Society. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/news-resources/projects/low-carbon-energy-programme/large-scale-electricity-storage/

The late UK Chief Scientific Advisor Professor Sir David MacKay said the same thing in a different way many years ago via his online book “Sustainable energy - without the hot air”. He used simple engineering calculations to show the impossibility of powering a modern industrial economy with intermittent weather-dependent renewables but his advice was wilfully ignored by our political class. In hindsight it is obvious that way back then they were already collaborating to wreck our energy infrastructure on the pretext of "climate change" at the behest of their globalist overlords. https://www.withouthotair.com/.

It is so obvious that trying to run the country with net zero fossil fuels using replacements which have useless EROEI ratings (Energy Return on Energy Invested) will lead to economic collapse and mass starvation. https://davidturver.substack.com/p/why-eroei-matters?utm_source=publication-search.

Another way of expressing energy gradient is EROEI. Here's a complimentary way of describing why it matters.

https://davidturver.substack.com/p/why-eroei-matters